Almir da Silva Mavignier

born 1925

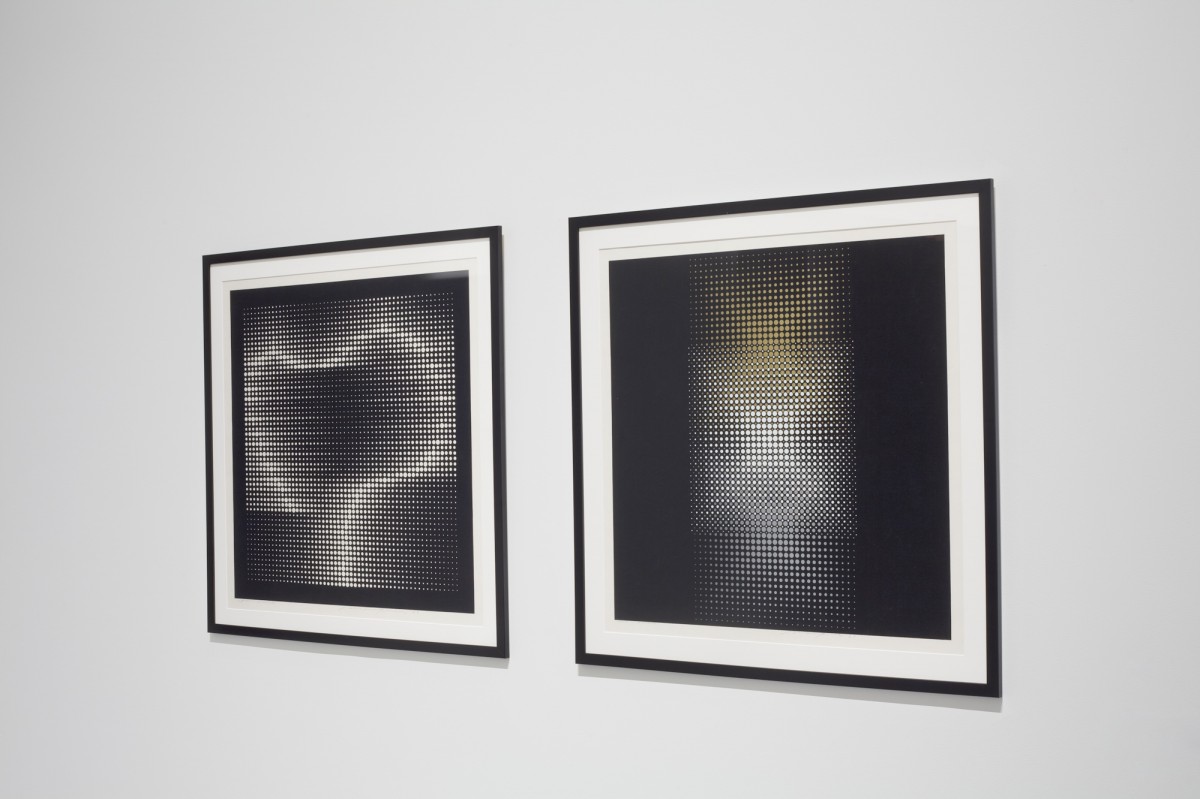

Almir Mavignier was known to express the opinion that the artist functions in the realm of the unknown. Much like other Brazilian artists his age, he let himself get swept away by the radical vision held by the Swiss artist Max Bill, whose retrospective was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in São Paulo in 1950. From today’s perspective, Bill was the spark that ignited an art revolution in Brazil. Art groups like Grupo Ruptura and Grupo Frente rose up in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, which practiced Concrete Art based on the rules of geometry and mathematics. In Europe, this current was formulated as a response to the individualist and spontaneous character of abstract expressionism. In Brazil, concretists set themselves up against the traditions of figurative painting. The fascination with Bill and his postulates was so strong that two years after viewing the exhibition, Mavignier moved to Ulm, where he matriculated into the School of Design co-founded by the Swiss artist. The curriculum was meant to follow the Bauhaus-inspired, holistic approach to art education, however the faculty’s ambitions in this regard were even loftier. The focus wasn’t only on the integration of art with crafts and technology, on the creation of a complex tool for the study of visual communication. Students studied psychology, sociology, economics and systems thinking. A scientific approach to art, much like the belief that science is a window to the future, was very much present in Mavignier’s artistic practice. When he was still a student in Ulm, he began experimenting with mesh geometry. In his paintings, it figured not simply as an arrangement of lines, but, rather, as dots indicating their point of intersection. This technique was inspired by Mavigner’s professor, Helene Nonne-Schmidt, in the spirit of Paul Klee’s statement that the point at which lines intersect is an Energy point that collects and absorbs the dynamism released by the remaining elements. The dots that appear in his works are of varying sizes, at times one of another color would be added to the lattice. The minimalism applied to the background, the varying size of the letters and colors, the use of a single line or a lattice, all came together to produce a complex visual effect. Most of all, the multiplicity of dots significantly altered the geometric structures that would otherwise be recognizable to the eye, while remaining relegated to a component. Mavigner called this mechanism the process of discovering the “geometry of the unknown.” The precise application of dots on the canvas generated a number of optical illusions, such as the impression of depth, a distorted perception of the intensity of color or the feeling of vibration. Mavignier understood his experiments as art founded upon data theory, which postulated that a work of art is a symbol made up of micro-symbols that build a network based on strictly defined rules. The measure of artistic integrity is in the unforeseen effects that come about in the net bound by these rules. When we view Mavignier’s paintings today, they closely resemble prototypes illustrating the flow of data across computer systems.

Almir Mavignier (born 1925) is a visual artist, graphic designer, pedagogue. Prior to emigrating to Europe from his native Brazil, he and Abraham Palatnik founded a studio that held painting classes for patients of psychiatric hospitals. At the time, he was interested in Gestalt theory and began making connections between science and art. After completing his studies at the Ulm School of Design, he set up his own graphic design studio and also became affiliated with the Zero group, an experimental collective from Düsseldorf that ran a magazine of the same name. The group was invested in the idea that art should no longer serve as the domain of emotions and subjective expression. Mavignier believed that art and design are related, distinguished only by their goal, which is why his career as a designer and an artist developed in parallel. Mavignier is behind an original technique of poster art, which is based on the repetition of a single graphic, geometric element. The resulting pattern, and the product it’s meant to advertise, is easily remembered. At the beginning of the 1960s, he began collaborating with the Yugoslavian community of artists active in the field of Concrete Art and Op Art. He contributed to the organization of the first New Tendencies international exhibition in Zagreb.