Milan Dobeš

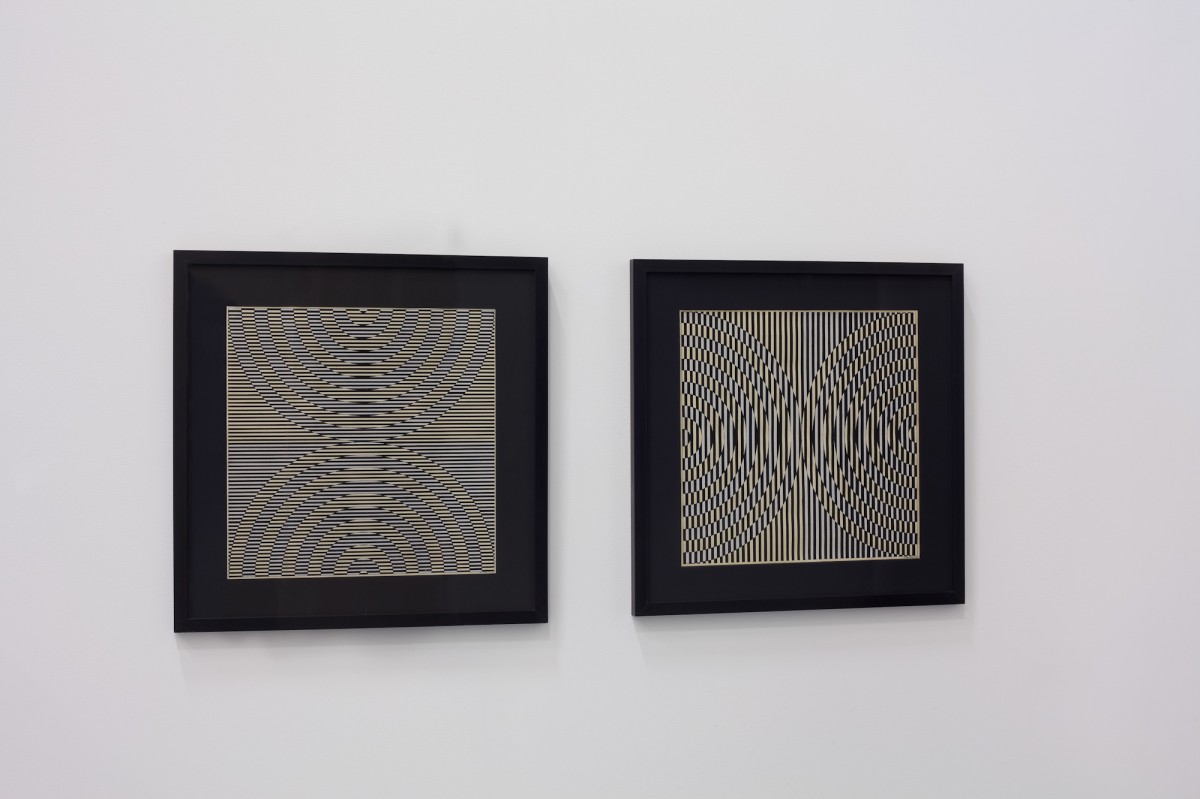

When the French critic Frank Popper was attempting to convince Milan Dobeš that the optical illusions in his paintings were entirely different than anything he’d seen up to that point from op-art artists, Dobeš didn’t seem particularly surprised. “How could they resemble anything if I didn’t have any knowledge that there were artists who were also going deeper into issues of perception, movement and light, just as I was?” This is how the artist recalled his response many years later. Geometric abstraction didn’t have a significant following in communist Czechoslovakia even when it was no longer necessary for art to comply with the government’s doctrine of socio-realism. He was frequently denied the opportunity to exhibit his work as a solo show and he wasn’t invited to any group shows either. At one point, he was kicked out of the local Artists’ Association on the premise that his work was in foreign to Czechoslovakian culture. The situation underwent a reversal when in 2966 the Soviet-Czechoslovakian Friendship Union unexpectedly set up a show for him in Prague. He exhibited his op-art paintings there, works that were founded upon his extensive research into the nature of the circle. The characteristic element of his style was the repetition of a single geometric motif and establishing a rhythm for this action around a single point, which the artist called the “point of instability” – a point that disturbs an established order, bringing a dynamic energy into the painting. The eye of the viewer automatically focuses on this perturbation, experiencing a range of illusions as a result: movement, depth or the impression that certain elements of the painting were rising up out of the canvas. In addition, the exhibition featured several of his sculptures and optical-kinetic objects. More than 20 years later Dobeš summed up his approach in this field in the manifesto Dynamic Constructivism, claiming that from the beginning of time, art has been the kingdom of geometric forms that have gradually escaped from the rigors of representation, achieving their formal purity only in constructivism. Art that took up the notion of movement had to clash with this order of forms in some way. It wasn’t until technological progress provided artists with new tools to bring them to life. Through the use of small-scale motors, it became possible to set certain elements of a sculpture, object or installation into motion, while simple electrical systems allowed for their synchronisation. For Dobeš, technology wasn’t a fetish, but a medium that allowed him to broaden the range of his visual experimentation. His kinetic objects created dynamic systems of interaction between geometric forms made of simple elements, such as conclave metal sheets that reflected and disfigured elements that were driven by an engine, along with lightbulbs, which added reflective light effects. In an interview, Dobeš recalls that before he made his first optical-kinetic works, he worked as a designer of lighting systems for hotels and restaurants. In working on these part-time commissions, he realised that functional design objects could be used in the field of art. As a true pioneer of kinetic art in Czechoslovakia and one of the most original representatives of the genre in Central-Eastern Europe, he eventually gained international renown and was invited to show his works at the fourth edition of the Documenta Biennale in Venice or Poland’s Nowe Tendencje. When in 1968 the troops of the Warsaw Pact entered Czechoslovakia, the Mánes Gallery in Prague happened to be showing an exhibition titled The New Sensibility, presenting the works of artists in the field of geometric abstraction and kinetic art, including works by Dobeš. He has recounted how Soviet soldiers stormed the gallery and were completed disoriented by the art. A sentinel manned Dobeš’ work as there were fears it was actually a radar.

Milan Dobeš (born 1929) is a Slovakian artist and pioneer of kinetic art in the former Czechoslovakia. He turned away from the imposed call for art to fit into the conventions of socio-realism and began exploring expressionism instead, then cubism, which ultimately led him to constructivism and experimentation with optical illusions. He created paintings, as well as sculptures and optical-kinetic objects. Some of his works were made to improve the public spaces of cities like Bratislava or Osaka. He also spent a year touring across the United States with the American Wind Symphony Orchestra, putting together an optical-kinetic arrangement to their compositions. He is among the most well-known names in Czechoslovakian art.